|

By BECKY JOHNSON

Staff writer The Enterprise Mountaineer

If ever there was a tree designed with early

Appalachian settlers in mind, it was the American chestnut.

It grew tall and straight, and it was easy

to split cracking evenly and predictable and making perfect shingles and split

rail fences, The tree was strong and durable, yet light and its even grain

meant boards did not warp when drying.

The American chestnut was

termite-resistant and did not rot in damp soil, making it good for fence posts

and railroad ties and telegraph poles. Its beautiful color made it a favored

wood for interior paneling, cabinets, bedposts and staircases.

Pigs where turned out every fall to fatten

on the threes’ plentiful nut harvest. The nuts fell so thick on the forest floor

they where racked up and sold by the wagon load for flour and sugar and stored

all winter as food.

One out of every four trees used to be a

chestnut. They grew up to 120 feet tall and more than 12 feet wide, making

excellent timber.

When the chestnut blight hit the Southern

Appalachians in the 1920s killing every tree in its path, it was like having

the rug yanked out from under the dinner table for many Appalachian settlers.

They not only lost the best tree they had for making their own homes, fences, barns,

and furniture, but they also lost the income from the nuts they had depended

upon.

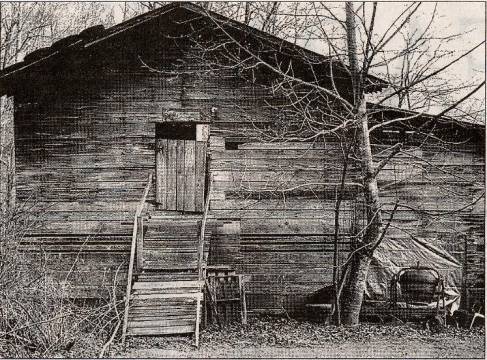

“When you think of the value American

chestnut had for split rail fences, for log homes, barns, all your furniture,

your musical instruments, from the casket to the cradle,” said Paul Gallimore

of Sandy Mush. “It’s a beautiful wood. It’s got such versatility as indoor and

outdoor.”

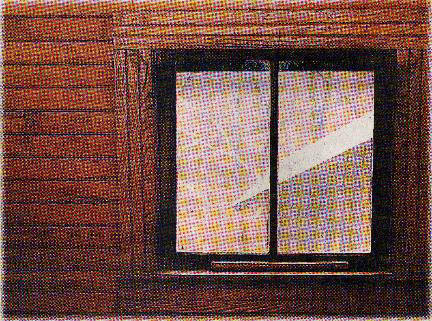

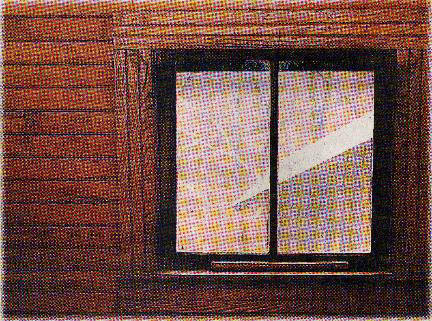

Gallimore

toured his Sandy Mush property, circling a 85-year-old barn made of chestnut,

pointing out old chestnut fence post and admiring the still glowing chestnut

paneling on the interior walls of a 1917 home.

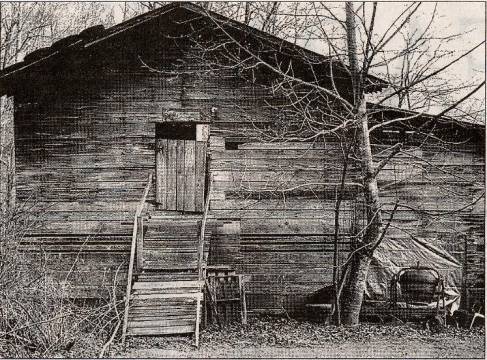

Behind Gallimore’s house is an old cabin

make of hand-hewed chestnut logs.

We found a number of different stumps

from the American chestnut,” Gallimore said, making a sweeping gesture at the

woods that covered the hillside behind the home. “It would have been

everywhere. There were some places here that had 100 acres of pure American

chestnut. It was the dominant tree species here up until the beginning of the

20the century.”

The largest American chestnut ever

documented in North America, with a diameter of 17 feet, was in the Francis

Cove area of Haywood County.

Chestnut trees were rot- and

termite-resistant because they had high tannin levels. Tannin, which is present

in most trees in smaller doses, was the chemical used to tan leather. It was

leached from the bark and wood of the chestnut and made into a dark, bitter,

brine. The leather was soaked in the mixture for several days.

“Chestnut had an incredible value because

of its tannin,” Gallimore said. “The tannin value of the chestnut exceeded the

value of the wood.”

One of the Gallimore’s goals today is

reseeding the mountains with American chestnut. Gallimore runs the Longbranch

Environmental Education Center just over the Haywood County line in Sandy Mush

and has been a leader in the American Chestnut Reforestation Project.

For

the last 20 years, scientists and chestnut enthusiasts with the American

Chestnut Foundation have been working to come up with an American chestnut tree

that is blight resistant.

The blight came to America on a Chinese

chestnut in the early 1900s and spread quickly, claiming all the American

chestnuts of the Southern Appalachians by 1930. While Chinese chestnuts are

blight-resistant, they are short, knotty, spreading trees, with none of the

timber quality that make the American chestnut useful.

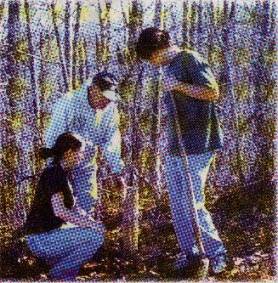

When the blight killed American chestnuts,

it left the root of many trees intact, Gallimore said. Tiny American chestnut

shoots can be found sprouting up from the trunk of a fallen American chestnut.

The shoots only grow a few years before succumbing to the blight, but have been

important in breeding a new blight-resistant tree.

Scientist have been crossing American

chestnut trees with Chinese chestnuts to get a tree that has all the admired

qualities of American chestnut, but has just enough Chinese chestnut in it to

make it blight-resistant.

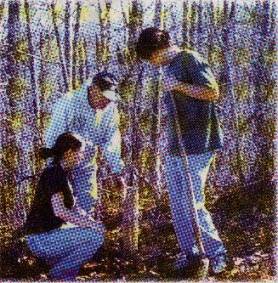

By genetically crossing American chestnut

with Chinese chestnuts, scientist have ended up with a tree that is about 85

percent American chestnut, according to scientists with the American Chestnut

Foundation. Last month, 18 of these trees were planted in Haywood County in the

Rough Creek watershed area above Canton. The trees will be monitored to see how

well they grow and if they stay blight-free.

Another group of American chestnuts –

about 130 – was planted by Gallimore on a private preserve in Beaverdam in

November. That group also will be monitored for its blight resistance. If all

goes well, Gallimore hopes landowners will be able to get seedlings from these

trees and plant them on their own property.

”We’re

interested in letting landowners know these trees are available,” Gallimore

said. “Our goal is to see the trees get planted out.”

It will be another ten years before there

are large numbers of blight-resistant American chestnut seedlings ready to pass

out to landowners.

“2010 and afterwards, we’ll be shipping

seeds to normal people,” said Forest McGregor, development director with the

American Chestnut Foundation. “There were 4 to 10 billion American chestnuts

killed by the blight. We will consider our project finished when there are

blight-resistant trees out there making their own babies. We’ve got to plant

millions and millions of trees to get to that point.

The hope is that, once the seedlings are

ready, people will take them and plant them. Those trees will drop their own

seeds, as well as cross pollinate with Chinese chestnuts, and eventually reclaim

their place as king of the Appalachian forest and the most useful of all trees

|